Research Highlights

Research Confirms Collective Nature of Quark Soup’s Radial Expansion

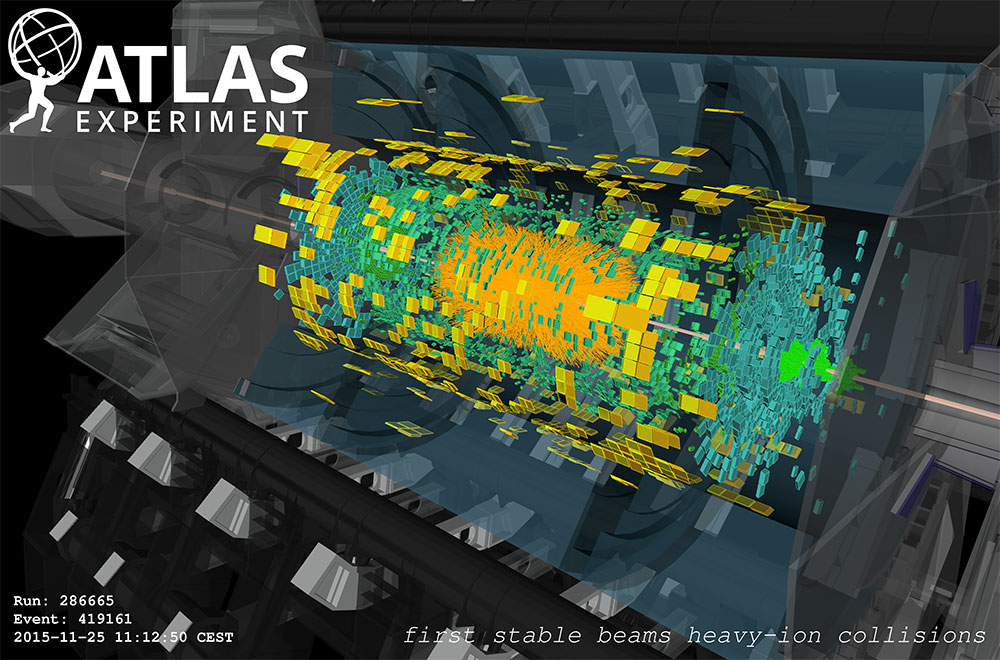

Scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and Stony Brook University played leading roles in the analysis of heavy ion collisions at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) that provide evidence that a pattern of “flow” observed in particles streaming from these collisions reflects those particles’ collective behavior.

The LHC is the world’s most powerful particle collider, located at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, and the measurements reveal how the distribution of particles is driven by pressure gradients generated by the extreme conditions in these collisions, which mimic what the universe was like just after the Big Bang.

The research is described in a paper published in Physical Review Letters by the ATLAS Collaboration at the LHC.

The international team used data from the LHC’s ATLAS experiment to analyze how particles flow outward in radial directions when two beams of lead ions — lead atoms stripped of their electrons — collide after circulating around the 17-mile circumference of the LHC at close to the speed of light.

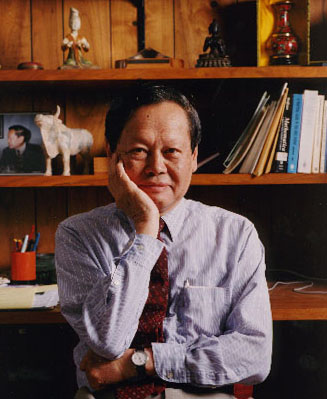

“Earlier measurements revealing that particles flow collectively from heavy ion collisions were central to the discovery of the quark-gluon plasma at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC),” said Jiangyong Jia, a physicist and professor at Stony Brook University and Brookhaven Lab, where RHIC operates as a DOE Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research. Jia conducts research at both the RHIC and the LHC and led the new ATLAS analysis.

“The new results from ATLAS, while confirming the fluid-like nature of the QGP (quark-gluon plasma), also reveal something new because the type of flow we studied, ‘radial’ flow, has a different geometric origin from the ‘elliptic’ flow studied previously, and it is sensitive to a different type of viscosity in the fluid system,” Jia said.

The findings offer new insight into the nature of the hot, dense matter generated in these collisions, with temperatures more than 250,000 times hotter than the Sun’s core. These extreme conditions essentially melt the protons and neutrons that make up the colliding ions, setting free their innermost building blocks, quarks and gluons, to create a quark-gluon plasma.

Stony Brook Researchers Redefine Capacitor Behavior at the Nanoscale

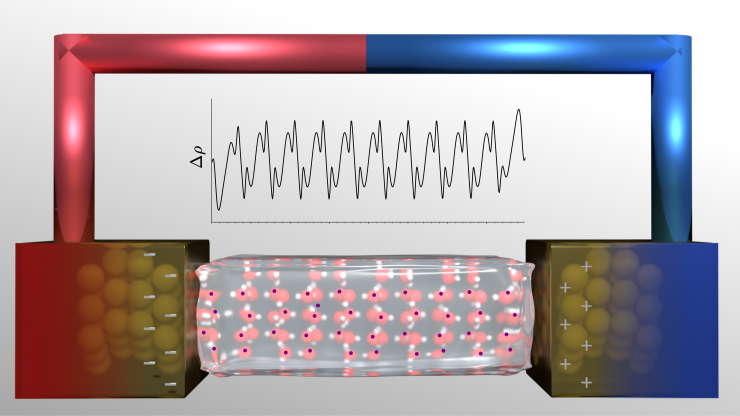

Stony Brook University researchers led a new study published in Physical Review Letters that overturns long-standing assumptions about how capacitors operate when engineered at the nanoscale, offering a clearer scientific foundation for future nanoscale electronic devices.

Capacitors—core components of modern electronics—store electrical charge between metallic electrodes separated by a dielectric material. While their performance is well understood at macroscopic scales, conventional models break down at the nanoscale, where the material properties assumed in standard equations are no longer well defined. These discrepancies pose significant challenges for interpreting the dielectric response of ultrathin materials and for designing reliable nanocapacitors.

To address this problem, the SBU team developed a quantum-mechanical framework that unambiguously separates the contributions of the electrodes and the dielectric. The new protocol establishes fundamental limits on how small a capacitor can be made and provides a reliable approach for evaluating the intrinsic behavior of nanoscale insulating materials.

Demonstrating the method on ultrathin ice, the researchers found that its electronic response to electric fields is essentially indistinguishable from that of bulk ice, despite extreme confinement. The result resolves discrepancies between theoretical predictions and experimental measurements of ice films only a few molecules thick.

“This work offers a pathway to accurately characterize ultrathin dielectric materials using first-principles calculations,” said Ph.D. candidate Anthony Mannino, the study’s lead author. “With a clearer understanding of nanoscale dielectric behavior, we can improve device design and better interpret experimental data.”

The study was led by Mannino, together with fellow Ph.D. candidate Kedarsh Kaushik and visiting student Graciele M. Arvelos, under the direction of Professor Marivi Fernández-Serra at Stony Brook University’s Institute for Advanced Computational Science (IACS), where Mannino is a recipient of the IACS Graduate Fellowship.

Astronomers Sharpen the Universe’s Expansion Rate, Deepening a Cosmic Mystery

A team of astronomers using a variety of ground and space-based telescopes including the W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea, Hawaiʻi Island, have made one of the most precise independent measurements yet of how fast the universe is expanding, further deepening the divide on one of the biggest mysteries in modern cosmology.

Using data gathered from Keck Observatory’s Cosmic Web Imager (KCWI) as well as NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) the Very Large Telescope (VLT), and European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) researchers have independently confirmed that the universe’s current rate of expansion, known as the Hubble constant (H₀), does not match values predicted from measurements from the universe when it was much younger.

The finding strengthens what scientists call the “Hubble tension,” a cosmic disagreement that may point to new physics governing the universe.

“What many scientists are hoping is that this may be the beginning of a new cosmological model,” said Tommaso Treu, Distinguished Professor of Physics and Astronomy at the University of California Los Angeles and one of the authors of the study published in Astronomy and Astrophysics.

“This is the dream of every physicist. Find something wrong in our understanding so we can discover something new and profound,” added Simon Birrer, Assistant Professor of Physics at the Stony Brook University and one of the corresponding authors of the study.

The team’s measurement currently achieves 4.5% precision — an extraordinary feat, but not yet enough to confirm the discrepancy beyond doubt. The next goal is to refine that precision to better than 1.5%, a level of certainty “probably more precise than most people know how tall they are,” noted Martin Millon, postdoctoral fellow at ETH Zurich and the third corresponding author of the study.

Research Groups and Connected Research Centers